The rhythmic thrum of a sewer cleaner truck’s high-pressure pump is the heartbeat of municipal maintenance, yet its effectiveness hinges on an operator’s nuanced understanding of an invisible variable: jetting pressure. Far from a simple “max power” equation, identifying the ideal pressure is a sophisticated calculus blending fluid dynamics, material science, infrastructure vulnerability, and real-world obstinacy. Applying too little force leaves clogs intact; too much risks catastrophic pipe damage, costly collateral harm, or dangerous blowbacks. This intricate balance transforms pressure selection from a dial-setting into a critical engineering decision impacting system longevity, operator safety, and public utility resilience.

The Physics of Filth: Understanding Pressure Fundamentals and Clog Dynamics

Effective jetting transcends brute force; it harnesses focused hydraulic energy strategically. Core principles define this interaction:

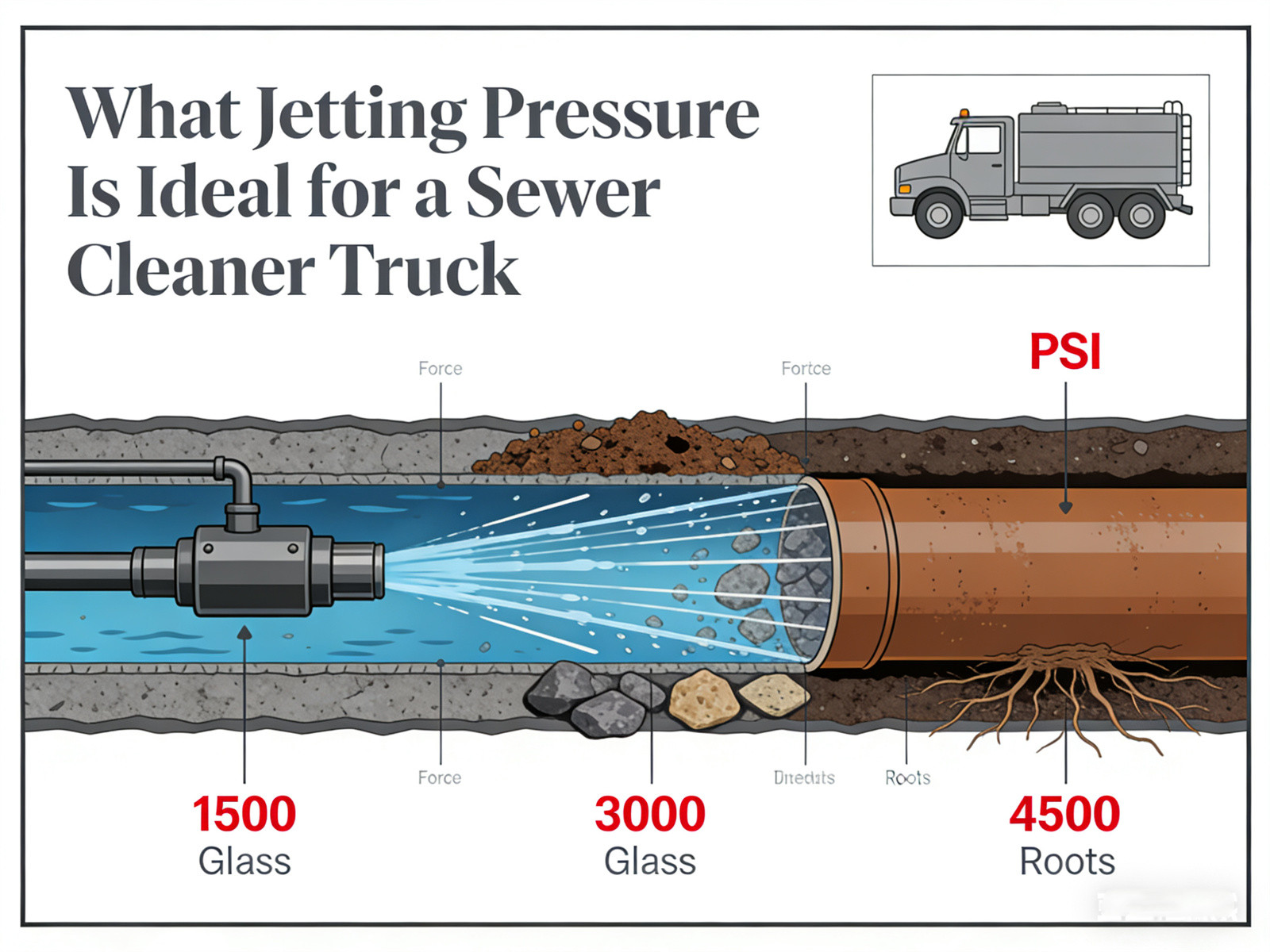

- Dynamic Pressure vs. Flow Rate: Pressure (measured in PSI or Bar) determines the intensity of the water stream’s impact, while flow rate (GPM or L/min) dictates the volume of water delivered. Optimal cleaning requires synergizing high PSI for cutting/shearing with sufficient GPM to flush debris effectively. A high-PSI, low-GPM jet might punch a small hole in a grease clog but fail to clear the surrounding mass, leading to rapid re-occlusion.

- Nozzle Trajectory & Impact Mechanics: Specially engineered nozzles convert pump pressure into directed kinetic energy. Forward jets punch through blockages; rear-facing jets propel the hose and scour pipe walls; rotary nozzles provide omnidirectional cleaning. The nozzle’s orifice size, jet angle, and design (e.g., chain knockers for roots) dramatically influence the effective force delivered to the target material. Velocity, derived from pressure and orifice restriction (V = √(2P/ρ), where ρ is fluid density), is the true agent of cleaning – higher velocity translates to greater impact energy on the obstruction.

- Clog Composition Dictates Strategy: A monolithic concrete intrusion demands radically different pressure than fragile root masses, grease bergs, or sediment dunes. Brittle materials (hardened grease, certain roots) may shatter under high impact, while ductile clogs (thick fats, rags) require sustained shearing force. Understanding the suspected clog type through inspection (CCTV) or experience is paramount for initial pressure estimation.

Navigating the Variables: Determining the “Ideal” Pressure Sweet Spot

No universal “ideal” PSI exists; it’s a dynamic target defined by context:

- Pipe Material, Age, and Condition:

- Vintage Clay or Concrete: Highly susceptible to joint damage and cracking. Conservative pressures (1200-2000 PSI) are mandated, relying more on the nozzle technique and flushing flow.

- Ductile Iron: More resilient but can suffer from internal corrosion, weakening walls. Moderate pressures (2000-3000 PSI) are typical, with care near joints.

- PVC, HDPE, and Modern Composites: Generally tolerate higher pressures (up to 4000 PSI or more for robust mains), but manufacturer specifications and installation quality are absolute constraints. Older PVC joints remain vulnerable.

- Pipe Diameter and Layout: Smaller diameters (4-8″) require lower pressures than large mains (12″+), as force concentration is higher. Sharp bends, tees, and laterals create points where misdirected high-pressure jets can erode pipe walls or damage connections – pressure often needs to be reduced when navigating these sections.

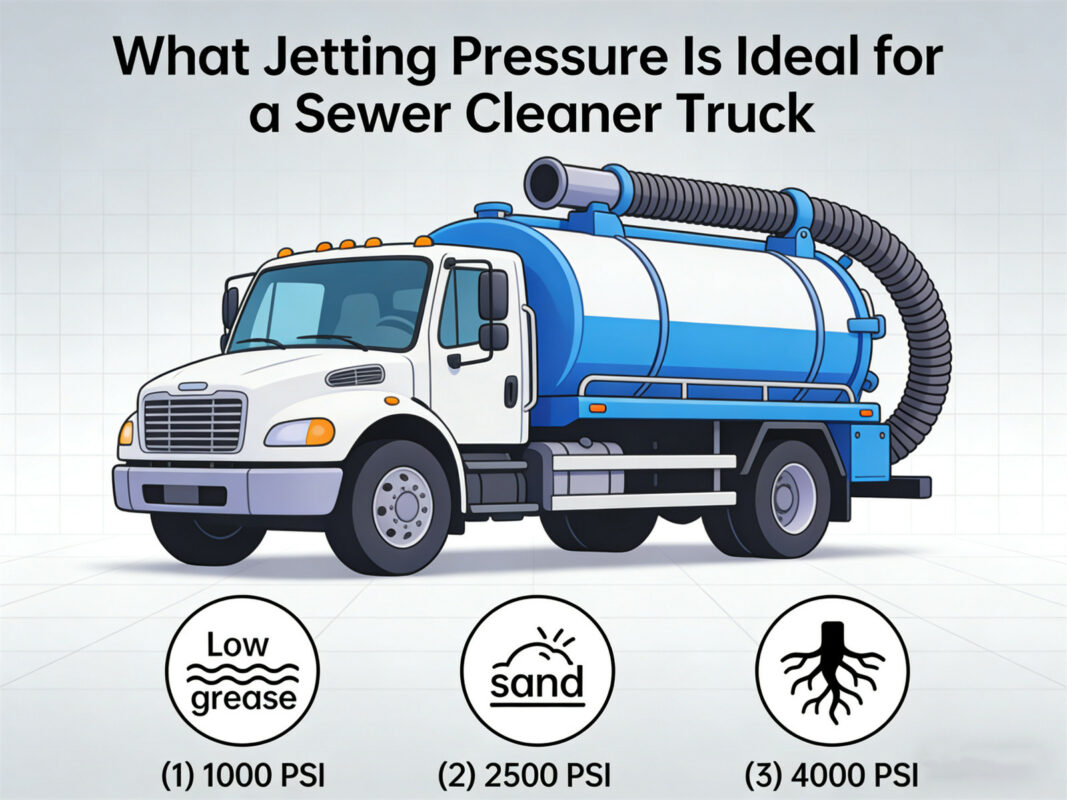

- Nature and Severity of the Blockage:

- Soft Sediment/Sand: Lower pressures (1500-2500 PSI) with high flow effectively flush.

- Grease/Fats: Moderate to high pressures (2500-3500 PSI) combined with hot water (if available) are needed for melting and shearing; rotary nozzles excel here.

- Root Intrusions: Require specialized cutting nozzles and typically higher pressures (3000-4000+ PSI) combined with chain flails or root saws to sever and extract masses.

- Hard Debris/Construction Waste: Extreme caution is needed. High pressure might shift material but risks damaging pipes or creating worse jams. Often requires mechanical extraction via vacuum truck first, followed by lower-pressure flushing.

- Safety and Environmental Imperatives: Pressure choices directly impact risks. Excessive force can fracture pipes underground, leading to sinkholes; cause blowbacks at cleanouts injuring operators; or propel debris dangerously. Near sensitive structures or shallow utilities, pressure must be scaled down significantly.

The Machine Matters: Matching Pressure to Truck Capabilities and Configuration

The sewage truck itself dictates the practical pressure envelope:

- Pump Specifications: The truck’s high-pressure pump has rated maximum PSI and GPM capabilities. Never exceed manufacturer ratings, as this risks catastrophic pump failure and voids warranties. Modern pumps often feature variable displacement pistons allowing independent adjustment of PSI and GPM within their performance curves.

- Hose Diameter, Length, and Condition: Smaller diameter hose (e.g., 1/2″) maintains higher pressure at the nozzle over longer distances but delivers lower flow. Larger hose (e.g., 3/4″ or 1″) allows higher GPM but experiences greater pressure loss (friction loss) over extended runs. Longer hose deployments inherently reduce nozzle pressure – operators must compensate or reposition. Damaged or kinked hose drastically reduces performance and creates safety hazards.

- Water Tank Capacity and Recovery: High-pressure jets consume massive water volumes. A larger tank supports sustained cleaning but adds weight. Truck-mounted water reclaim systems filter and reuse jetted water, extending operational range but adding complexity. Pressure settings must align with available water volume – running the tank dry mid-cleaning is ineffective.

- Vacuum Power Integration: True efficacy combines jetting and extraction. The vacuum truck component must possess sufficient CFM (airflow) and inches of Mercury (inHg) (vacuum power) to efficiently evacuate the debris dislodged by the jetter. Insufficient vacuum leaves loosened material in the pipe, creating a downstream mess or rapid re-clogging. Pressure application should be synchronized with vacuum capability.

Operational Art: Techniques for Maximizing Effectiveness at Safe Pressures

Mastering pressure involves skilled execution, not just dial settings:

- The Progressive Escalation Principle: Always start cleaning at LOW pressure (e.g., 1000-1500 PSI). Gradually increase pressure only as needed, constantly monitoring nozzle progress via the hose feed rate and camera (if used). Sudden high pressure on an unknown obstruction is reckless.

- Nozzle Selection & Maneuvering: Choosing the right nozzle is force multiplication. Use forward jets to penetrate blockages, then switch to rear or rotary jets to scour walls once penetrated. Oscillate or rotate the hose manually near pipe walls to distribute force and prevent localized erosion. Avoid excessive “hammering” on a single spot.

- Distance-to-Target Optimization: Nozzle effectiveness diminishes rapidly with distance from the obstruction due to jet diffusion. Maintain the nozzle as close as safely possible to the clog for maximum impact force without risking nozzle entrapment. Camera guidance is invaluable here.

- The Flushing Imperative: High-pressure cutting phases must be interspersed with high-volume, lower-pressure flushing cycles (using the truck’s auxiliary flush pump or bypass valves). This removes dislodged debris from the cleaning path, prevents nozzle burying, and allows visual assessment of progress. Flushing is as crucial as jetting pressure itself.

Pressure-Related Pitfalls: Troubleshooting Common Cleaning Failures

Understanding how pressure manifests in failures refines operator judgment:

- Insufficient Cleaning Power (Clog Persists): Often misdiagnosed as needing more pressure. Check: Was flow rate adequate alongside PSI? Was the correct nozzle type used? Was debris effectively flushed away (vacuum truck suction adequate)? Was the hose advanced close enough? Root masses often require specialized cutters, not just higher PSI.

- Excessive Debris Left Behind: Primarily a failure of flushing protocol or insufficient vacuum truck extraction power, not insufficient jetting pressure. Ensure high-GPM flushing cycles are performed regularly and vacuum CFM/inHg matches pipe size and debris load.

- Hose Snaking/Whipping/Kinking: Often caused by excessive pressure combined with nozzle misalignment in the pipe or sudden pressure surges when a clog clears. Reduce pressure immediately if hose behavior becomes erratic. Use hose guides or stabilizers in large pipes.

- Nozzle Entrapment: Getting the nozzle stuck behind a collapsed pipe, severe offset joint, or within dense debris is a major hazard. High pressure exacerbates this by driving the nozzle deeper. Prevention lies in cautious advancement, camera guidance, and readiness to reverse flow instantly using the pump’s reversing function or auxiliary valves.

Beyond the Hose: Integration and the Future of Pressure Management

The future lies in smarter pressure application, not just higher numbers:

- Sensor Fusion & Real-Time Feedback: Emerging systems integrate CCTV cameras directly into jetting nozzles or sleds, providing operators live visuals at the cleaning head. Combined with inline pressure sensors monitoring actual PSI/GPM at the nozzle (not just at the pump), and pipe material/scaling data, this enables truly dynamic pressure adjustment optimized for the immediate environment.

- Automated Pressure Modulation: Algorithms are being developed to automatically adjust PSI and GPM based on sensor input – reducing pressure instantly when traversing a fragile clay joint or scaling up when encountering dense root masses, all within predefined safe limits for the pipe segment. This reduces operator cognitive load and prevents inadvertent over-pressure.

- Advanced Nozzle Design: Innovations focus on cavitation jets (using controlled bubble collapse for powerful localized cleaning with potentially lower overall line pressures) and pulsating jets that deliver high-impact bursts more effective on certain materials than constant streams, reducing total hydraulic load.

- Integrated CSCTRUCK Municipal Platforms: The convergence of high-pressure jetting, powerful vacuum extraction, advanced water filtration/reclaim, and sophisticated control systems into unified CSCTRUCK Municipal units represents the cutting edge. These platforms offer seamless switching between jetting and vacuum modes, optimal water management for sustainability, and centralized data dashboards correlating pressure, flow, vacuum metrics, and CCTV visuals. This holistic approach maximizes cleaning efficacy while embedding safeguards ensuring pressure application remains precisely calibrated to the infrastructure’s tolerance and the task’s specific demands, transforming raw hydraulic power into a precisely measured surgical tool for maintaining the arteries of modern sanitation.

Mastering jetting pressure remains the defining skill in sewer cleaning, an ongoing dialogue between hydraulic force and infrastructural fragility, demanding respect for both the power wielded and the hidden networks it serves.